NARCISSISM AND D. G. ROSSETTI'S

THE HOUSE OF LIFE

BY

ARTHUR CYRUS JOHNSTON

© Copyright by Arthur Cyrus Johnston 1977, 2006

All Rights Reserved

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Figures

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I:

The Soul and the House of Love

CHAPTER II:

Darkened Love and Wild Images of Death

CHAPTER III:

The Soul's Sphere of Infinite Images

CHAPTER IV:

Belated Worshiper of the Sun

CHAPTER V:

Youth and Fate

CHAPTER VI:

Sathana, Sirens, Newborn Death and Hope

CHAPTER VII:

Personifications of the Self and

The Year's Turning Wheel

BIBLIOGRAPHY

TABLE OF FIGURES

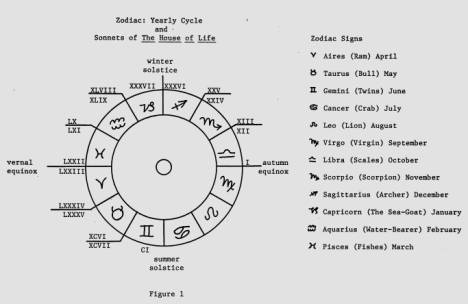

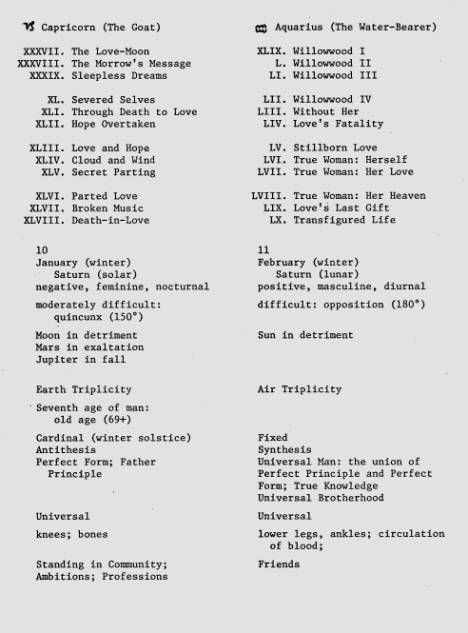

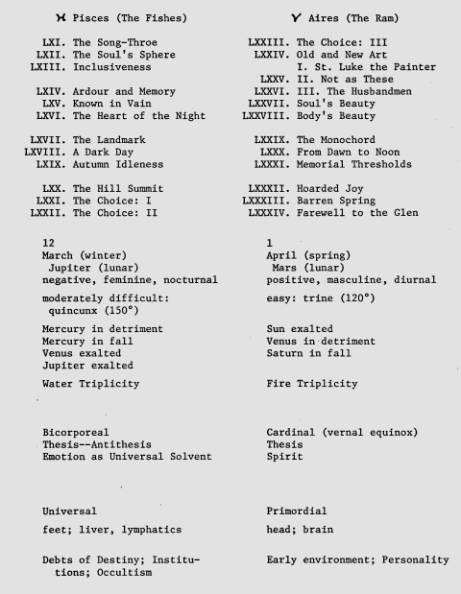

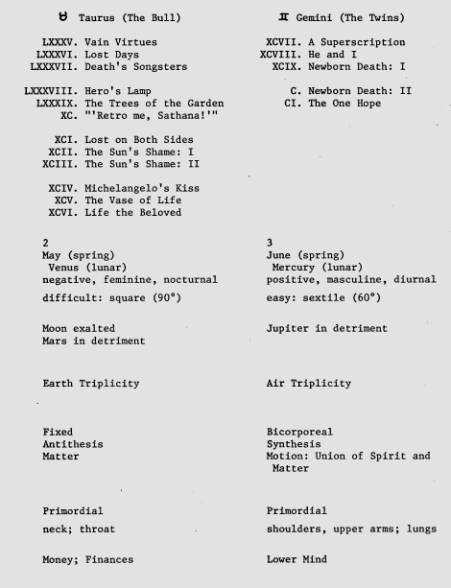

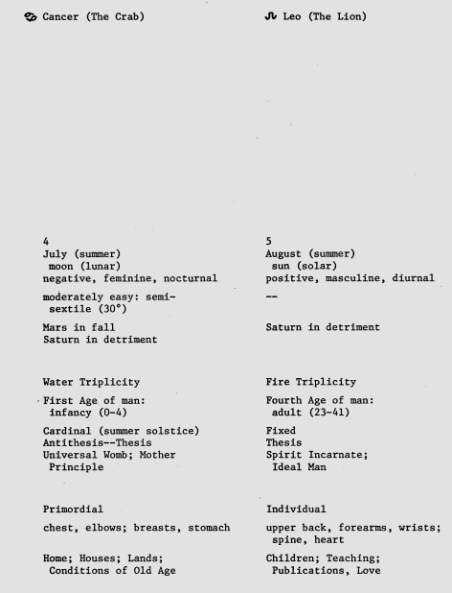

Figure 1: Zodiac: Yearly Cycle and Sonnets of

The House of Life

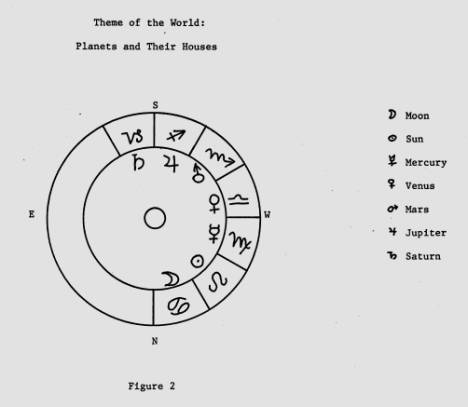

Figure 2: Theme of the World:

Planets and Their Houses

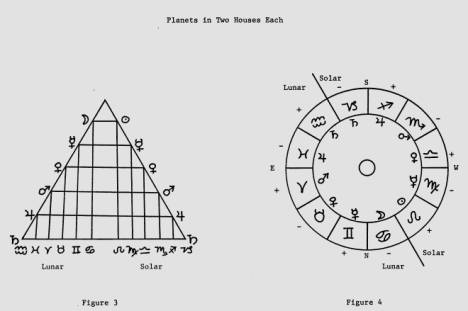

Figure 3: Planets in Two Houses Each

Figure 4: Planets in Two Houses Each

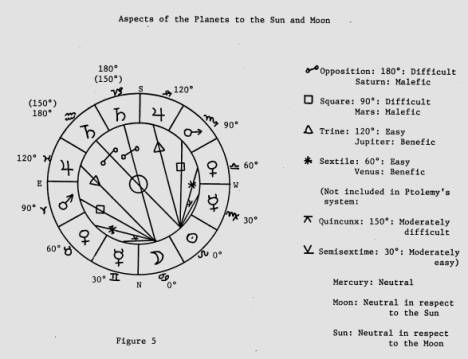

Figure 5: Aspects of the Planets to the Sun and Moon

Figure 6: Four Functions of the Mind

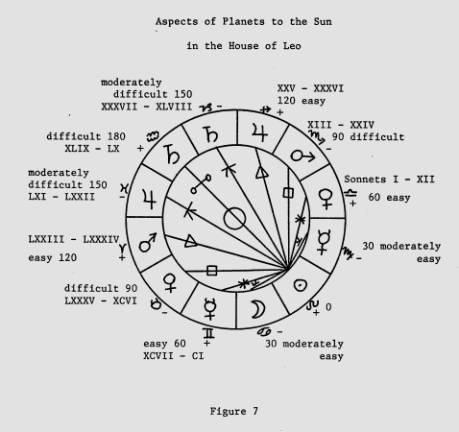

Figure 7: Aspects of Planets to the Sun in the House of Leo

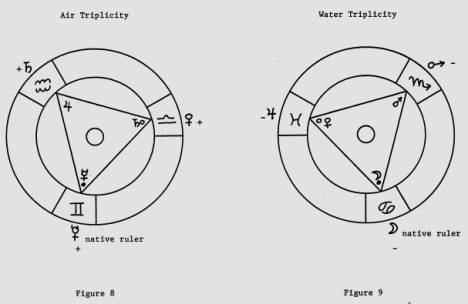

Figure 8: Air Triplicity

Figure 9: Water Triplicity

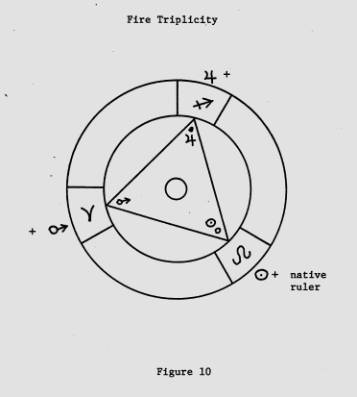

Figure 10: Fire Triplicity

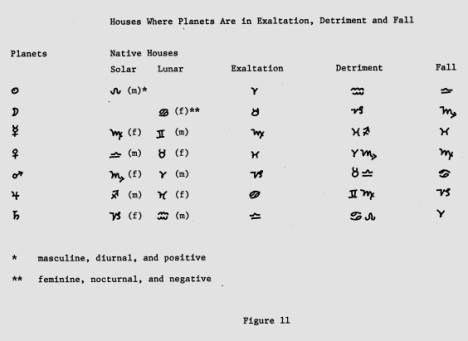

Figure 11: Houses Where Planets Are in Exaltation

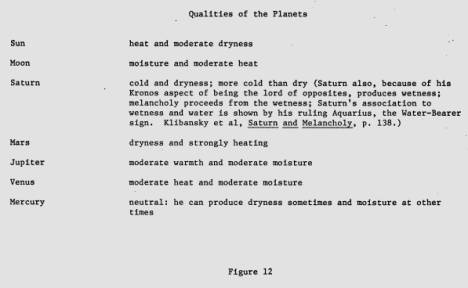

Figure 12: Qualities of the Planets

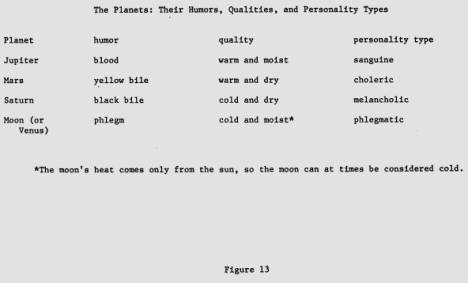

Figure 13: The Planets: Their Humors, Qualities and Personality Types

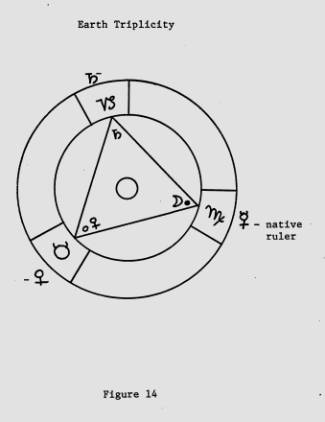

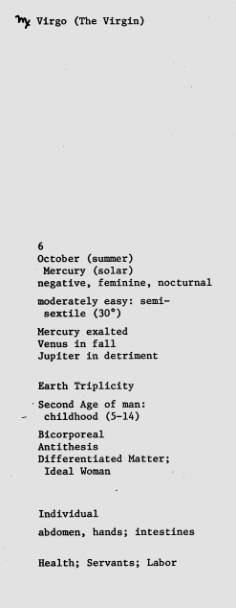

Figure 14: Earth Triplicity

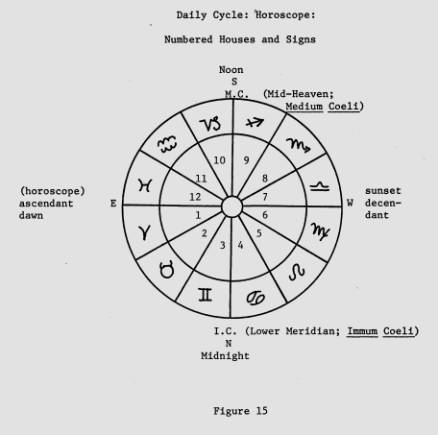

Figure 15: Daily Cycle: Horoscope: Numbered Houses and Signs

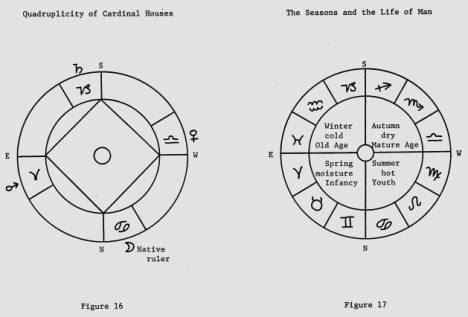

Figure 16: Quadruplicities of Cardinal Houses

Figure 17: The Seasons and the Life of Man

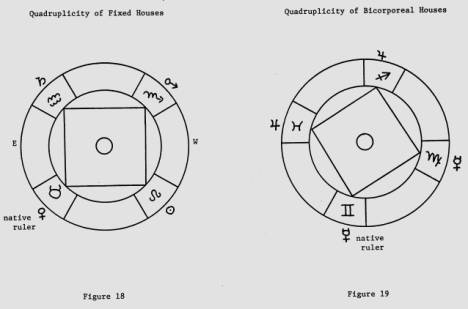

Figure 18: Quadruplicity of Fixed Houses

Figure 19: Quadruplicity of Bicorporeal Houses

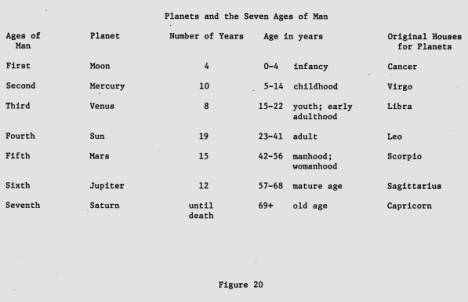

Figure 20: Planets and the Seven Ages of Man

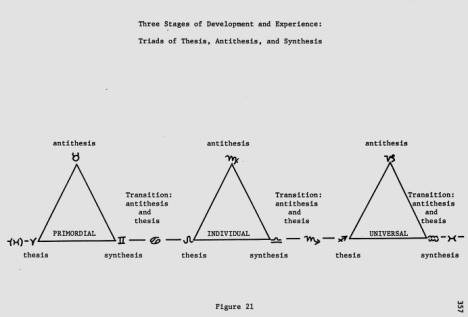

Figure 21: Three Stages of

Development and Experience:

Triads of Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

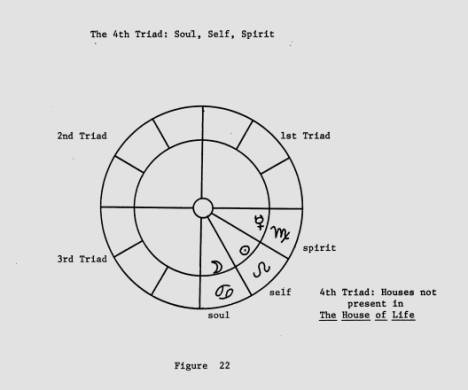

Figure 22: The 4th Triad: Soul, Self, Spirit

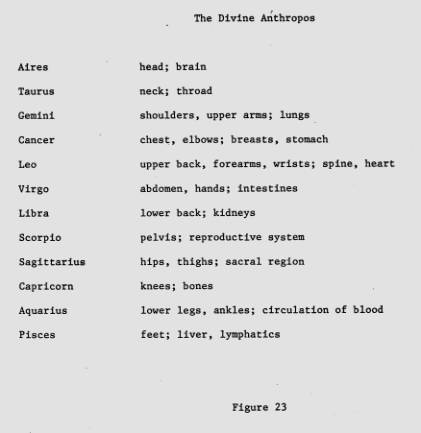

Figure 23: The Divine Anthropos

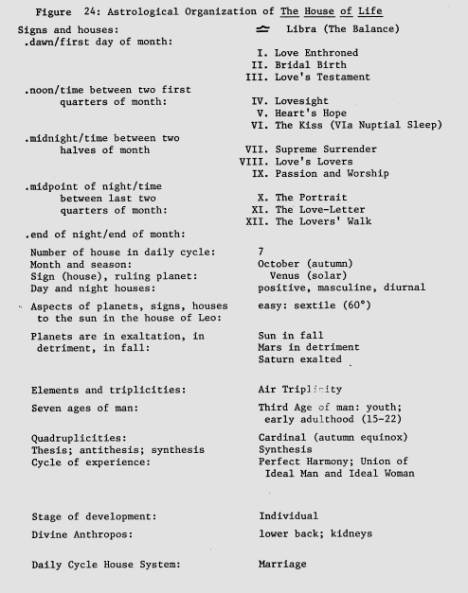

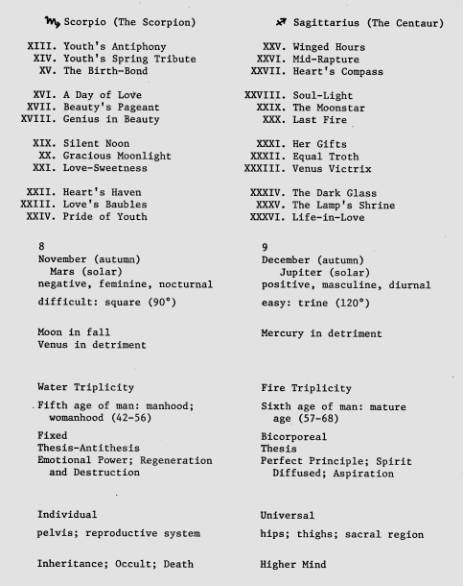

Figure 24: Astrological Organization of The House of Life

Introduction

The Willowwood sonnets appear at the center of The House of Life and are crucial for any reading of the meaning and structure of the sonnet sequence. The critic Douglas J. Robillard sees the Willowwood sonnets not only central to the pattern of the work but "a pivot on which the whole structure turns.1 A close examination of these pivotal sonnets will reveal many parallels with the Narcissus myth as narrated by Ovid in Metamorphoses. The basic situation in the Willowwood sonnets is that of Narcissus. The narrator of the sonnets and Love are sitting beside a "woodside well" and are "Leaning across the water."2 Soon their "mirrored eyes" meet "silently in the low wave." The narrator is in a state of grief because he is separated from his second Beloved, who was first specifically mentioned in "Life in Love" (XXXVI), and because his first Beloved had died. In grief and sadness, the narrator sheds tears and beneath his eyes and Love's appear those of his Beloved on whom all his love is centered. Narcissus, too, focused all his love on one person in the form of an image of himself and aggressively repulsed the advances of all girls, boys, and particularly Echo who desperately loved him.

Both the setting of the isolated grove with its pool deep as a well and silver-clear and the place where Love and the narrator lean over a well have an unearthly quality. In Ovid's account, there are no shepherds, shegoats, cattle, birds, or beasts; not even a leaf ever ruffles the surface of the pool: and the sun never burns hotly on the shadowed spot.3 In the opening Willowwood sonnet, no animate forms of life other than the narrator and Love appear. The only sounds are those of Love's voice and his lute; Love's song promises to reveal a secret. A sense of strangeness and mystery pervades the atmospheres of both settings. In his defense of his poetry from Robert Buchanan's attack, Rossetti drew attention to the essential quality of the opening Willowwood sonnet by calling it "a dream or trance."4

In another version of the Narcissus myth, the image in the pool is not Narcissus' but that of his identical twin sister who had died. Pausanias presented this version in his A Description of Greece.5 He rejects the self-love theme and adopts a more realistic attitude toward the myth. After his twin sister died, Narcissus found relief from his loss by loving his reflected image, which reminded him of his sister. Pausanias however does not quite explain the strangeness involved in this grief leading to Narcissus' death or the possible implications of an incestuous love.

The narrator of the Willowwood sonnets, like this Narcissus, is grieving over his separation from his Beloved and ultimate loss of her. Willowwood as depicted by Love in his trance-like song is a place where the narrator and his Beloved's former selves of past days stand mournfully like a "dumb throng" (L). Willowwood in this way parallels Narcissus' isolated grove which becomes the site where he dies. Paull Franklin Baum in his edition of The House of Life defines Willowwood as being "a grave, with a well or fountain, sacred to those who have loved and lost and cannot forget." 6 Narcissus, too, can not abandon his love or forget even though he consciously desires to: "If I could only / Escape from my own body! if I could only-- / How curious a prayer from any lover-- / Be parted from my love!" (Ovid 72).

Unlike the narrator of the Willowwood sonnets, Narcissus dies from his longing and his love. He may have even committed suicide by either refusing to eat or by drowning himself in the pool. Narcissus' grove became his grave, and he was mourned by all his sisters of the river, by the sisters of the forest, and, most of all, by Echo. Narcissus will never be forgotten because of his myth and because of his becoming immortalized as the Narcissus flower (Ovid 72-73). Echo, too, has an immortality. Her body fades away completely, leaving her voice, which continues to exist as an echo that responds to voices of living things. Echo is similar to the first Beloved in that she and her love are also rejected for another by the one whom she loved. Narcissus never loved her at all, whereas the narrator of The House of Life loved his first Beloved intensely.

The myth of Narcissus involves as much violence, aggression, betrayals, and death as it does love and worship of beauty. Narcissus' very being came about through violence. His father, who was the river God Cephisus, raped Liriope after he dragged her into his river. Narcissus violently rejects all suitors. When Echo confessed her love for him, Narcissus repulses her embraces: "'Keep your hands off,' he cried, 'and do not touch me! / I would die before I give you a chance at me"' (Ovid 69). Outward violence like that in the Narcissus myth is rarely present in Rossetti's sonnet sequence; however, betrayal and death appear frequently. In "The Love-Moon" (XXXVII), the narrator shows some traces of guilt over his finding a new love so soon after the death of the first Beloved. Death appears in the introductory sonnet in the image of Charon being paid his coin for his ferrying a dead soul across the river Styx and in the first sonnet "Love Enthroned" where Life wreathes "flowers for Death to wear." Though absent for a time, Death reappears constantly and finally asserts his domination of all in the final sonnets.

Equally important for the Narcissus myth and The House of Life is Fate. After being raped by Cephisus, Liriope, Narcissus' mother, consults Tiresias about the fate of her newborn because he is a man who has experienced being both sexes, knows the truth and can foretell the future. She wants to know how long her child will live. Tiresias' answer is that Narcissus will live a long time "if he never knows himself" (Ovid 68). Tiresias' prophesy did come true. Fate and self-knowledge assume as important roles as do love and death in Narcissus' life. Nemesis, the goddess of Fate, answered a prayer by a rejected boy suitor of Narcissus by granting the boy's wish that Narcissus would "Love one day, so, himself and not win over / The creature whom he loves!" (Ovid 70). It was Nemesis who prepared the isolated grove and the pool that held the fateful attraction for Narcissus (Ovid 70). Rossetti entitled Part II of the sonnet sequence "Change and Fate." The very title of The House of Life suggests an astrological association and a concomitant involvement of fate. Numerous references to fate appear throughout the sonnets. Fate reaps a harvest in "Supreme Surrender" (VII); the moon is "the journeying face of Fate" in "Secret Parting" (XLV); and "o'ershadowed Troy with fate" appears in "Death's Songsters" (LXXXVII). Fate plays a larger role in the narrator's life than just these references indicate.

Other close connections exist between the Narcissus myth and the Willowwood sonnets. These parallels and links of similar motifs and themes are not limited to the Willowwood sonnets but radiate throughout the whole sonnet sequence. Many critics do not find any organizing principle within The House of Life, whereas others see the biographical elements as the only unifying forces. Some critics recognize an organizing principle for Part I but despair at the task of finding this or some other unifying principle for Part II. A few critics find a definite unity in the sonnet sequence. 7 The concept of narcissism which stems from the myth of Narcissus offers an organizing principle on all levels such as themes, motifs, and structural patterns. Sigmund Freud, Otto Rank, and others have supplied psychological meanings to the Narcissus myth, and Carl Jung and his followers have added archetypal meanings to it. Narcissism has many complex facets and even the psychoanalysts are not in complete agreement about its precise definition and psychological applications on clinical and theoretical levels. 8 Literary men and the average man have both adopted the term narcissism and applied it in the overall meaning of "self-love." Specific core elements of the concept and the myth, however, do exist and will prove useful in exploring the themes, motifs, images, content and structural patterns of The House of Life. The astrological implications of the title of the sonnet sequence will have to be considered also as a possible source for an organizing principle, particularly if there are strong links between astrology and narcissism.

NOTES

1"Rossetti's 'Willowwood' Sonnets and the Structure of The House of Life," Victorian Newsletter, #22 (1962), 6.

2Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The House of Life, A Sonnet Sequence, ed. Paull Franklin Baum (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1928), p. 138. This edition follows that in The Collected Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, edited by William Michael Rossetti (London: Ellis, 1911); henceforth all references to the sonnets in The House of Life will be from Baum's edition and will be cited in the text by Roman numerals.

3Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. Rolfe Humphries (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1957), p. 70. Henceforth all citations will be in the text.

4The Stealthy School of Criticism," The Pre-Raphaelites, ed. Jerome H. Buckley (New York: Random House, 1968), p. 465.

5Pausanias's Description of Greece, trans. J. G. Frazer (New York: Biblo and Tannen, 1965), 1, p. 483.

6Baum, The House of Life, p. 141.

7Clyde de L. Ryles in his essay "The Narrative Unity of The House of Life," (Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 69 (1970], 241 257) has summarized the basic important scholarship on the unity or disunity of the sonnet sequence up to 1970. Frederic E. Faverty in The Victorian Poets: A Guide to Research (2nd ed. [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968] gives more details on basically the same critics and their works.

The prominent exponents of biographical reading as a means of organizing Rossetti's sonnet sequence are Frederick M. Tisdel ("Rossetti's 'The House of Life,"' Modern Philology, 15 (1917], 257-276); Ruth C. Wallerstein ("Personal Experience in Rossetti's House of Life," PMLA, 42 [19271, 492-504); and Oswald Doughty (A Victorian Romantic: Dante Gabriel Rossetti [London: Frederick Muller Ltd., 1949]).

In 1962, Douglas J. Robillard ("Rossetti's 'Willowwood' Sonnets and the Structure of The House of Life") saw the Willowwood sonnets as the central organizing element of Rossetti's 1870 and 1881 versions, although Robillard did not think the final work was successful. Robillard, however, abandoned the biographical method.

William E. Fredeman ("Rossetti's 'In Memoriam': An Elegiac Reading of The House of Life," Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 47 [1965), 298-341) saw no chronological or biographical reading possible. The work has all the organizing elements of an elegy.

Other critics have pursued other organizing principles such as J. L. Kendall's "infinite moment" as theme ("The Concept of the Infinite Moment in The House of Life," Victorian Newsletter, #28 [Fall, 19651, 4-8); Robert D. Hume's inorganic form as later practiced by T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound ("Inorganic Structure in The House of Life," Papers on Language and Literature, 5 [1969], 282-295) ; and Henri Talon's symbolism ("Dante Gabriel Rossetti, peintre-poèite dans La Maison de Vie," Études Anglaises, 19 [1966], 1-14; D. G. Rossetti: THE HOUSE OF LIFE: Quelques aspects de l'art, des thèmes.et du symbolisme [Archivès des Lettres Modernes, Minard, 1966]).

Clyde de L. Ryals in "The Narrative Unity of The House of Life" presents the organizing principle of Rossetti's work as a complete dramatis personae of the soul, specifically the soul's pilgrimage through life in a journey of "logical discontinuity" or in the form of "the symbolist technique of juxtaposing without links."

Dissertations that deal specifically with organization of The House of Life are: Maja Zakrezewska, "Untersuchungen zur Konstrucktion und Komposition von DGRs Sonnettenzyklus The House of Life" (Freiburg, 1922); Stephen Joel Spector, "The Centripetal Journey: The Poetry of Dante Gabriel Rossetti" (University of Pennsylvania, 1969)--this explores the Victorian consciousness in Rossetti's work and the centripetal journey into the self in The House of Life; Roger Carlisie Lewis, "The Poetic Integrity of D. G. Rossetti's Sonnet Sequence, The House of Life" (University of Toronto, 1969)--Lewis sees The House of Life as similar to the structure of Tennyson's In Memoriam but differing in that Rossetti's work is cyclical rather than linear; Rufus Allen Pridgen, "Apocalyptic Imagery in Dante Rossetti's The House of Life" (The Florida State University, 1975)--for Pridgen, the apocalyptic imagery in Rossetti's work creates a unified vision, showing the experiences of an individual soul.

8Sydney E. Pulver, "Narcissism: The Term and the Concept," Journal of American Psychoanalytic Association, 18 (1970), 319-341.

CHAPTER I

The Soul and the House of Love

The Willowwood sonnets are the culmination of two love affairs of the narrator. Specifically, the image in the well water is that of the second Beloved shown as one of memory's figures that Love sings about in the second Willowwood sonnet. Generally, though, the image of the second Beloved has the characteristics of the first Beloved superimposed on it. Both in the Narcissus myth and in Rossetti's sonnet sequence, the emotion of love and the object of that love are central. In the Narcissus myth, the isolated grove and the mirror like pool assume great importance for the working out of Narcissus' love. The Narcissus myth, too, concentrates on Narcissus' overwhelming love for his own image to the exclusion of all external reality beyond the grove. Only his death brings about a separation from his beloved image, and even on the River Styx, Narcissus, for the last time, looks longingly at his image.1 In the form of the Narcissus flower, too, he leans over the water as he did in human form. 2 Through Echo are revealed the sufferings of complete separation of a lover from her object of love.

In Rossetti's sonnet sequence, the story of the narrator's love for his first Beloved matches the intense love and devotion of Narcissus, and like Narcissus' love, the narrator's love is ended by death, not his own as in the situation of Narcissus but in his Beloved's. The first thirty-six sonnets portray the narrator's love of his first Beloved and explicitly her death in the last sonnet of this division, "Life-in-Love" (XXXVI). The narrator's love for his first Beloved has many links with the mythical, psychological, and archetypal aspects of narcissism.

The narrator's attitudes toward his Beloved have irritated some of Dante Rossetti's critics, especially his first harsh critic, Robert Buchanan, who objected to Rossetti's mixing the spiritual with the material, or sensual. On specific occasions, Rossetti does blend the two. In "Lovesight" (IV), the narrator asks, "When do I see thee most, beloved one?" As part of a second rhetorical question, the narrator ends the question with the implied answer, "And my soul only sees thy soul its own?" The narrator's and the Beloved's souls, at this point, are fused into one. In the next sonnet, "Heart's Hope" (V), the narrator expands this oneness of soul to include her body, and by implication his too, and connects their love to God: "Thy soul I know not from thy body, nor Thee from myself, neither our love from God."

The same union of the narrator's soul and his Beloved's appears again in several other sonnets of this first thirty-six sonnet group. In "The Love-Letter" (XI), the narrator wishes he had been present--when his Beloved wrote the love-letter--for a particular moment: "When, through eyes raised an instant, her soul sought / My soul and from the sudden confluence caught / The words that made her love the loveliest." Since confluence means etymologically the flowing together of two streams, their two souls flow together to become one. The same confluence appears in "The Kiss" (VI) in the realm of emotions. The narrator feels himself a god when he kisses his Beloved, and their "life-breath" meets to fan their "life-blood, till love's emulous ardours" run "Fire within fire, desire in deity." The "Fire within fire," the mutual "life-breath," and their "life-blood"--all have flowed together to become one.

In Greek, the original term for soul is psyche. Etymologically, psyche means breath, principle of life, and life. The narrator's use of "life-breath" and "life-blood" in "The Kiss" (VI) touches upon this simplest definition of soul as an "immortal animating life force" that enters the body at the moment of conception or during pregnancy and that leaves the body at death. .3 Biologically, the genes carry this immortal substance, which does continue as long as offspring of the parents survive and reproduce in an unbroken chain. In "Love's Testament" (III), the narrator uses the word life to signify the union of both souls and bodies. The narrator tells his Beloved that following the will of Love, "thy life with mine hast blent," and then he murmurs, "I am thine, thou'rt one with me!" To be one with his Beloved means that both the souls and the bodies merge into one as was his desire in "The Kiss." Physically and on a purely rationalistic plane, bodies can not merge. Other concepts will be necessary then to explain the narrator's union with the Beloved. In "Youth's Antiphony" (XIII), the blending of the two souls and, again possibly, the bodies of the two lovers occurs while they talked to each other and Love "breathed in sighs and silences / Through" their "two blent souls one rapturous undersong." The verb breathed intensifies the meaning of "two blent souls" and implies the blending of the two bodies as happened in "The Kiss," where their "life-breath" was one.

Rarely in the first group of thirty-six sonnets do the body and the soul definitely separate from one another. In "Bridal Birth" (II), after death, the "bodiless souls" of the lovers become Death's children in a marriage of their souls in eternity. This view of the soul echoes the basic meaning of the soul as "an immortal animating life force" which leaves the body at death. It also points to a Gnostic view of the soul which will become important later in coming to understand fully Rossetti's concepts of the soul, body, and love.

Rossetti left no doubt about the importance of the soul for his sonnet sequence. Rossetti's introductory sonnet announces that the basic function of a sonnet is to reveal the soul: "A Sonnet" is a "Memorial from the Soul's eternity" and "A Sonnet is a coin: its face reveals / The soul." The word soul appears not only in this group of thirty-six sonnets but constantly throughout the whole sonnet sequence right up to the last sonnet where the soul prepares for death. Some critics have suggested that the sonnet sequence be renamed The House of Love. 4 Equally, the sonnet sequence could be called The House of Soul. In "The Orchard Pit," Rossetti used the phrase "the house of the soul" when the narrator of the story asks about the dead and the dead men's bodies, "Have they [i.e., the dead who surround the bodies] any souls out of those bodies? Or are the bodies still the house of the soul, the Siren's prey till the day of judgment?" 5

Since the introductory sonnet identifies the sonnet form with the soul and since the narrator of The House of Life believes his Beloved's soul is his very own when they are united in love, the Jungian concept of the anima becomes immediately apparent to a modern reader. The biographers and critics using the biographical approach to interpret the sonnet sequence and Rossetti's other poetry have extensively analyzed the three women of Lizzie Siddal, Fanny Cornforth, and Jane Burden. They are the women who naturally would receive Rossetti's anima projections. 6 In her article "The Image of the Anima in the Work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti," Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi explores the anima as it appears in several of his works. Clyde K. Hyder in "Rossetti's Rose Mary: A Study in the Occult" makes a passing reference to the anima figure. 7 Other critics may have used the anima term but not in any extensive manner.

Rossetti himself presents an anima figure in his short story "Hand and Soul." She appears to Chiaro in his own room at a time when he was deeply depressed over the course of his life. His room took on a mysterious atmosphere and a beautiful woman, wearing a green and grey dress, and with golden hair, appeared. Chiaro senses her to "be as much with him as his breath." Breath, as already indicated, has close associations with soul. Then the woman identifies herself as an anima figure, when she says, "I am an image, Chiaro, of thine own soul within thee. See me, and know me as I am." The woman as his soul then discusses Chiaro's relationship to God and the role of his painting in respect to God's demands. Only when Chiaro is above God, she believes, can he commune with God; she uses a narcissistic-like setting to describe this communion: "Only by making thyself his (i.e., God's] equal can he learn to hold communion with thee, and at last own thee above him. Not till thou lean over the water shalt thou see thine image therein: stand erect, and it shall slope from thy feet and be lost." To emphasize that she is only an image and not the soul itself, the woman asks Chiaro to paint a picture of her, and this portrait will relieve him of anxiety: "Do this (i.e., paint her picture]; so shall thy soul stand before thee always, and perplex thee no more."8

Carl Jung would agree with Rossetti's conception of a man's soul as an image. The anima and all archetypes are universal images. They stem from the "collective unconscious," which is the realm of religions, myths, rituals of cultures, or are répresentations collectives in Lévy-Bruhl's terminology.9 A Freudian interpretation of Rossetti's woman as a soul figure, however, would indicate that the woman was an incestuous love object which Chiaro had repressed into his personal unconscious and which has now returned to him because of the weakening of-his ego's unconscious power of repression. Jung broke away from Freud over this very question of whether an incestuous figure like the anima can have spiritual, or universal, meaning as opposed to the purely personal. 10 Jung's attachment of spiritual meaning to all archetypes-which represent the collective spiritual patterns and wisdom of all past generations--and to incestuous relationships such as mother and son, father and daughter, and brother and sister is important for understanding Jung's concept of the anima and for its application to the narrator's views of his anima figure, the Beloved, in The House of Life.

As the woman asserted in "Hand and Soul," she is only an image of the soul. Jung makes it very clear that the anima is not the soul but is a symbolic representation of it in the unconscious of a man. Since the man's conscious mind is masculine, anything that represents his unknown self, which is the unconscious, is feminine. The reverse is true for the woman; a male animus represents her unconscious as her conscious mind is feminine. The anima is not the pure divine soul which the Gnostics call "pneuma," "spirit," "Light," or "Logos" or what Jung calls "anima rationalis." Jung believes this definition of the soul to be dogmatic as it is a purely philosophical conception.

Jung reviewed the definitions of the soul in the past and completely rejected the Gnostic definition of the spiritual soul; this does not mean that he rejects the concept of a masculine spirit. Jung accepts the German word Seele, which means "quick-moving," "changeful of hue," "twinkling" and the Greek word psyche which means, besides soul, also butterfly, "which reels drunkenly from flower to flower and lives on honey and love." Jung thinks that primitives' belief that the soul is "the magic breath of life" or anima, and a flame is close to the real meaning of the anima figure. Jung's final definition which embraces all these definitions is that since the soul is a living being, it is thus "the living thing in man, that which lives of itself and causes life." The anima, too, like life, has a positive and a negative side. 11 Jung sums up his concept of the anima as an image of the soul by calling it "the archetype of life itself." 12 This Jungian concept of the soul closely matches the early Greeks' concept of the soul in that they too believed that the soul was life and, thus, was something that left the body upon death but was also intimately connected with the body. 13 Jung's anima concept, too, matches the narrator's in The House of Life, except that the negative side of the anima is excluded from his Beloved in this group of thirty-six sonnets. A negative side of the anima will make its presence felt in later sonnets.

The concept of the anima, however, is useless unless the process by which the anima becomes involved with the woman that a man loves is known clearly. Freud discovered this process in his psychoanalysis of his first patients. He called it transference. The patient has had an incestuous love and/or hate for a parent, brother, or sister as a child, particularly in the oedipal stage of development. This incestuous love was repressed into the personal unconscious. But as an adult, the patient projects the parent, brother, or sister image upon that of the psychoanalyst and then acts as if the psychoanalyst were the original incestuous object. Transference, or essentially projection, only works with unconscious contents. Therefore, to Freud all the contents of the unconscious that are eventually projected were originally introjected, or drawn, into the unconscious from the outside by the child in his family surroundings.

Jung agrees completely with Freud that a transference between two people occurs because of projections from the unconscious. Jung's work led him, however, to the discovery of a second source of projection, the collective unconscious. All that is of "a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals" belongs to the collective unconscious. Jung does not find this strange since he links the archetypes to instincts, which pursue their own goals. In fact, the "archetypes are the unconscious images of the instincts themselves, in other words they are patterns of instinctual behavior." 14 Jung reasons that the original personal incestuous objects of mother and father for the child could not be actively and continuously conscious in the first few years of life; it is impossible for the child, thus, to repress the mother-father sexual union and his oedipal desires. There must, therefore, have been an archetypal mother and father, or anima and animus, and their union, or syzygy, preexisting in the child's mind. The union of anima and animus can not be reduced to the personal mother and father. Behind the Freudian personal mother and father is a more ancient anima and animus that transcend the personal parents. 15

Jung considered the transference, or the projection, of the anima and animus onto people, ideas, and objects of such importance that he wrote his long article "Psychology of the Transference" to explain it. To Jung, the male alchemist was an excellent example of transference, for he projected his anima into the alchemical process so freely. Jung bases the transference on the archetype of the "mystic marriage" or "coniunctio," which is a union of the anima and animus; in paganism, it is called the hieros gamos. In the transference between the doctor and his patient, the archetype is activated and includes an incestuous relationship of father and daughter, mother and son, and brother and sister. Once the projection of the archetype of the divine pair is withdrawn from the personal parents, the transference, or projection, still exists between the patient and the doctor.16 In the alchemical process, which is Jung's model for the transference, the male alchemist can only project his anima, or feminine image of his soul, upon the Queen, who is in sexual union with the King, who in turn is an animus projection out of the unconscious of a female alchemist. 17 In The House of Life, the Beloveds would each receive an anima projection from the narrator's unconscious.

Jung states that the archetype of the sacred marriage of anima and animus is always linked to incest and to the family. In the most primitive situations between a man and a woman, the man projects his anima upon her and psychologically marries it. The live woman can be essentially ignored; the same can happen with a woman and her animus. The woman or man who is a stranger in the sense of not being of the same family as the one projecting is excluded from the union as much as possible. The libido, or love, consequently, is kept connected with the unconscious and in this way approximates the first situation where the archetype of sexual union of male and female was projected from the collective unconscious onto the personal family.

Jung drew upon a sociological study by a Jungian analyst for the terms "kinship libido" and "endogamous" relationships to describe the incestuous, or family, element of the spiritual union of male and female. 18 The incest taboo in a predominately matriarchal society is directed toward the brother and sister, whereas in a basically patriarchal society, the incest taboo, as Freud has outlined it in Totem and Taboo, is directed against mother and son. In a matriarchal society, kinship libido in the endogamous relationship may be combined with the libido directed toward strangers and thus an exogamous relationship. A brother and a sister in this system do not marry, but they each marry a cousin: a man marries his mother's brother's daughter, and he in turn gives his sister to his wife's brother. The exogamous element is maintained since every man belongs to his father's patrilineal family and can only take a wife from his mother's matrilineal family. This marriage system results in two brother and sister marriages crossing each other. The close cousin relationship of the man and woman satisfies the kinship libido, and the fact that they are strangers and not purely brother and sister satisfies the patriarchal exogamous system.

In the transference situation, Jung recognizes the reappearance of this cross-cousin situation where the doctor's anima is in an incestuous--or kinship, or endogamous--relationship with his patient's animus while they are also participating in an exogamous relationship as strangers, or non-blood related persons. Jung sees this situation not as a regression to the situation of group marriages but as a looking forward to an integration, or individuation, of the male and female components of the personality. Christianity promotes the exogamous form of relationship between man and woman, so they must marry strangers. In this situation, they project their anima and animus upon each other to satisfy their kinship or incestuous longings. The church provides the archetype of the mystic marriage of bride and bridegroom, but as this is pure dogma and not a vital component of life, the kinship, spiritual, and incestuous libido finds little satisfaction. 19

The narrator in The House of Life portrays the kinship libido of the endogamous relationship on both the family and spiritual planes in "The Birth-Bond" (XV). This sonnet appears after the height of the love experience in the first twelve sonnets and particularly those grouped around "The Kiss" (VI). In "The Birth-Bond" the narrator is in a reflective mood. A brother and sister were "born of a first marriage-bed" and subsequently the mother dies and the father remarries. Although the brother and sister act friendly to the children born of the second marriage, they have no real spiritual affinity with them. For each other, however, they have a "complete community" and a "silence speech." The narrator thinks that his love for his Beloved rests not only on a similar experience but was "One nearer kindred than life hinted of." The narrator felt this at his first sight of her. He exclaims, "0 born with me somewhere that men forget, / And though in years of sight and sound unmet, / Known for my soul's birth-partner well enough!" This concept of their relationship suggests both reincarnation and a strong spiritual kinship. The word "birth-partner" suggests, too, that they were twins. In a rationalistic interpretation of the spiritual affinity of the narrator for his Beloved, reincarnation is immediately rejected. Jung's concept of the anima, however, would be a realistic assessment of the narrator's instant recognition of his Beloved as being part of himself, both on the family relation of brother and sister and on the spiritual, or symbolic, level of archetypes. Indeed, this almost magical event would have the trappings of the ancient doctrine of reincarnation. All the numerous references to the narrator's and the Beloved's becoming one in soul and body in these first thirty-six sonnets receives another aspect in their "Birth-Bond," which is kinship on a spiritual level. The narrator's concept of his Beloved has moved quite close to Jung's anima concept through this additional emphasis on kinship of brother and sister. The same kinship of two kindred spirits appear in "Love-Sweetness" (XXI), where the two spirits of the lovers meet and feel "The breath of kindred plumes."

This theme of a spiritual kinship extending into past ages between a lover and his Beloved is not the only instance in Rossetti's works. In "Saint Agnes of Intercession," a young painter, the same age of nineteen as Chiaro in "Hand and Soul," saw when he was a child a picture of a beautiful woman named Saint Agnes painted by Bucciuolo d'Orli Angiolieri. This picture inspires him to learn to read well and stirs his interest in painting. As a young man, the painter meets a young woman named Mary Arden, whom he falls in love with because of her beauty and promises to marry her. To make himself famous, he decides to paint a serious subject that will "be wrought out of the age itself, as well as out of the soul of its producer, which needs be a soul of the age. 20 Mary, his Beloved, sat for the principal female figure. The painter as narrator quickly hints that this is an image of his soul, for he was submitting "his naked soul" to the public in his painting. At the exhibition of the picture, the painter meets a poet who is also a critic. Upon viewing the painter's picture, the poet-critic informs him that Mary Arden's picture matches exactly that of Angiolieri's St. Agnes. I

Unable to find the book with this picture, the painter eventually goes to Italy and finds the original painting which confirms the poet's words. Mary Arden and St. Agnes were identical. Even the painting styles of the young painter and Angiolieri were alike. Angiolieri had been in love with the beautiful woman who posed for his St. Agnes. Like Poe's "The Oval Portrait," Angiolieri painted his Beloved's picture as she was dying. Then to make the identity complete, the young painter looks at a self-portrait of Angiolieri and discovers that he and the four-hundred year old painter are identical in their facial features and form. This face-to-face confrontation with what his soul suspected made him reel. Rossetti still keeps the soul and the body closely connected; the painter as narrator writes, "I was as one who, coming after a wilderness to some city dead since the first world, should find among the tombs a human body in his own exact image, embalmed." 21

The young painter falls into a fever and that night dreamed that he met Mary before Angiolieri's picture of St. Agnes. She had a man beside her, who had his back to the young painter. The man was, of course, Angiolieri, who was holding a portrait of the young painter in the dress of four-hundred years ago. Angiolieri told the young painter that the picture was of neither of them and then his own face "fell in like a dead face." 22 After returning to England and falling seriously ill, the young painter does not know that Mary, like St. Agnes before her, has died, and at the end of the story, he goes to see her.

In this story, Rossetti presents the idea of reincarnation centered on an anima figure. The continuous use of images in paintings heightens the anima presence, as it did with Chiaro's beautiful soul image. The confrontation of the young painter and Mary Arden with their doubles in the paintings evokes the situation of transference described by Jung. There are two live people who project respectively their anima and animus onto paintings and people. In the young painter's dream, images were doubled as if between two sets of mirrors. The young painter's experience with his Beloved parallels Angiolieri's and in both cases the Beloved died as happened to Dante's Beatrice and to the narrator s first Beloved in The House of Life.

After Rossetti married Lizzie Siddal, he took her on a short trip to Paris, where he completed a drawing called "How they met Themselves." Lizzie Siddal was the model for the two women in the picture, who were identical to each other. The basic situation is like that in "The Birth-Bond" (XV) and "St. Agnes of Intercession" in that two twins confront each other. The meeting of these doubles signifies death for the couple according to the legend that if one meets his double he will die. 23 The young painter's and his Beloved's meeting of themselves in his dream was a forecast of her future death, although not his. In the light of Lizzie Siddal's early death after her marriage to Rossetti, his drawing this picture on their wedding trip was a strange occurrence. According to all the critics using a biographical interpretation of The House of Life, Lizzie Siddal is the narrator's first Beloved.

In many ways Lizzie Siddal was an anima figure for Rossetti. He pictured her as a Beatrice figure and painted her in this role, culminating in "Beata Beatrix," Rossetti's memorial picture for her. 24 Rossetti's anima figure of Lizzie Siddal has the features of a "Birth-bond" and the spiritual reincarnation in "Saint Agnes of Intercession." Rossetti wanted Lizzie to marry him on his birthday of May 12, as if to stress their kinship. 25 She was ill however and this did not happen. William Rossetti reported that Rossetti's first picture of Lizzie was a water-color called "Rossovestita," meaning "Red-clad." 26 Even this first picture has red and resembles the rose color present in the derivation of the family name of Rossetti. Rossetti had Lizzie to take up painting, drawing, and water coloring and even writing poetry. This made her identity closer to his. When they married and returned eventually to Chatham Place in London, they continued to live as before their marriage, and she followed his habits of painting all day and dining out at night. Rossetti's marriage changed his bachelor lifestyle very little. 27

Rossetti's relationship to Lizzie Siddal points to a more narcissistic kind of love than an ordinary object-centered love. In 1914, Sigmund Freud in his paper "On Narcissism: An Introduction" distinguished between the choice of an object on the basis of narcissistic libido or object libido. 28 Freud concluded that a person "may love:

(1) According to the narcissistic type:

(a) What he is himself (actually himself).

(b) What he once was.

(c) What he would like to be.

(d) Someone who was once part of himself." 29

This kind of love is a form of identification and involves narcissistic libido.

Freud calls the other kind of love which entails object libido "anaclitic type," meaning object love where the two objects are perceived as separate beings. Thus a person "may love

(2) According to the anaclitic type:

(a) The woman who tends.

(b) The man who protects." 30

The basic characteristic of anaclitic type of love is that the person who is loved is conceived as separate, whole, and individual. The person loved has both good and bad features; in this sense, they are whole. But in narcissistic love objects, the person loved is never complete in the sense of being both good and bad or imperfect and perfect at the same time. 31 In narcissistic love, the persons who are loved are not whole objects but are parts or functions of the self. Heinz Kohut, who is leading the investigation of narcissism in Freudian psychoanalysis, calls narcissistically chosen love objects, self-objects. 32 All the listings under Freud's narcissistic choices for a person to love are parts of the person's own self.

The narrator of The House of Life has identified completely with his Beloved, calling her soul his own and being one with her in body and soul. He even feels a kinship like a brother and sister relationship and a spiritual kinship that evokes concepts of reincarnation. All these relationships of union and identity suggest an equality between them. But very soon in the first thirty-six sonnets it becomes clear that most of the time there is no equality between the two lovers. "The Lamp's Shrine" (XXXV), the next to the last of the thirty-six sonnets, presents their basic relationship most clearly and shows the narcissistic aspects of the narrator's love. The narrator states, "Sometimes I fain would find in thee some fault" but then he asks rhetorically, "Yet how should our Lord Love curtail one whit / Thy perfect praise whom most he would exalt?" The narrator finds his Lady perfect and thus idealizes her completely, much as did Petrarch his Laura and as did the renaissance sonneteers their ladies at high moments. The title of the sonnet indicates that the narrator's Beloved is a lamp giving forth light and that he is creating a shrine for it. He becomes her worshiper as he was in "Mid-Rapture" (XXVI) where her gaze absorbed his "worshiping face." As light from a lamp in "The Lamp Shrine," she lights his "heart's low vault." The narrator, as worshiper, is in the subservient position and feels unworthy when contrasted to her. She is like "fiery chrysoprase" and he like "deep basalt." Her heart is a "flashing jewel" and his a "dull chamber" where her jewel will shine. The narrator-sums up his attitude in the last line when he says, "My heart takes pride to show how poor it is." The Beloved, however, is under the power of Love.

She is "Love's shrine" ultimately. By worshiping her, the narrator pays homage to Love. The "Lord Love" would not wish to "curtail one whit" the Beloved's "perfect praise" because he wishes to "exalt" her. "Love's Testament" (III) proclaims the same idea. The narrator's Beloved is "clothed with his [i.e., Love's] fire"; her heart is "his testament." Her breath is "the inmost incense of his sanctuary." She receives "grace"; the narrator "the prize" of his Beloved; but Love obtains "the glory." In the following "Lovesight" (IV), the narrator continues his worship of Love. He ends a question with "the spirits of mine eyes / Before thy face, their altar, solemnize / The worship of that Love through thee made known?" The emotion of love is more important than the individual object of that love.

At other times, the Beloved becomes not only equal to Love but Love himself and even beyond him to the essence of the universe itself. In "Heart's Compass" (XXVII), the narrator opens the sonnet with "Sometimes thou seem'st not as thyself alone, / But as the meaning of all things that are / A breathless wonder, shadowing forth afar / Some heavenly solstice hushed and halcyon." He concludes the octave with saying that she is "the evident heart of all life sown and mown." For the narrator she gives significance and meaning to everything, and she is the source, or the emotional center, of all life. These concepts closely fit the general definition of the soul as being life itself and life cannot move without the impetus of the emotions, particularly love. In western culture, dominated by patriarchal, or masculine, values, the emotions--the feeling function in Jung's four-functions concept--are dominated by the mother or anima archetypes. 33 Since a man's unconscious is basically feminine to offset his predominately masculine consciousness, this is not surprising. The narrator of "Heart's Compass" (XXVII) wonders that since his Beloved has all the characteristics of Love which he has already enumerated, "is not thy [i.e., his Beloved's] name Love?" and immediately affirms it is.

In this sonnet, the Beloved is considered his "Heart's Compass" to guide him through life and all its meanings. In "Gracious Moonlight" (XX), his Beloved is also a dominating force and guide in his life. He wonders:

Of that face

What shall be said,--which, like a governing star,

Gathers and garners from all things that are

Their silent penetrative loveliness?

Her attributes of beauty dominates the narrator's attitude in this sonnet. In "Her Gifts" (XXXI), the narrator gives a litany of praise of her "High grace," "sweet simplicity," her glance, her "thrilling pallor of cheek," her mouth, her neck, which is "meet column of Love's shrine / To cling to when the heart takes sanctuary," her hands, and her feet. Her name is like the sacred name of Yahweh in the Old Testament or other gods whose names must not be spoken except by the elect. For primitives and now for man in general to possess a name is to possess power over the object. 34 For this reason, the narrator admonishes, "Breathe low her name, my soul." The narrator's attitude toward her name further shows his worshiping attitude toward her and Love.

No matter whether his Beloved is subservient to, or equal to, or the same as, or superior to Love, the narrator is apparently the humble worshiper who has no gifts of his own. In "Equal Troth" (XXXII), the narrator expresses his inequality to his Beloved, despite the title which means equal faithfulness. He asks, "how should I be loved as I love thee?" and describes himself as "graceless, joyless, lacking absolutely / All gifts that with thy queenship best behove." As in the other sonnets, she is "throned in every heart's elect alcove, / And crowned with garlands, culled from every tree." In essence, by "Love's decree," her garland crowns have "All beauties and all mysteries interwove" among them. She rebukes the narrator, accusing him of saying her love is not equal to his. But the narrator tips the scales again and puts her "heart's transcendence" over his "heart's excess"--that is, quality over quantity--and makes her love more than a "thousandfold" his.

The narrator continues the same attitude of deference and lowliness in comparison to her in "The Dark Glass" (XXXIV). He says, "Not I myself know all my love for thee." His love is of such excess that it is beyond comprehension. Then in the sestet he asks, "Lo! what am I to Love, the lord of all?" Already the Beloved and Love have been equated as one in "Heart's Compass" (XXVII). The narrator compares himself to "One murmuring shell," an image that will again appear in later sonnets to signify lowliness, and "One little heart-flame." A key image in the sonnets, and particularly in this one, is the sea. It represents the vastness of life, the unknown, the immortality beyond life. The emotion of love itself in this sonnet is considered "the last relay / And ultimate outpost of eternity" which by implication is beyond the "loud sea." Love gathers the narrator up as he would a small sea-shell on the shore of life.

Paradoxically, the narrator at other times feels equal to the Beloved and at one with her. This is seen in their union where he states typically in "Heart's Hope" (V), "Thy soul I know not from thy body, nor / Thee from myself, neither our love from God." And at times as in "The Kiss" (VI), he feels like a god under her spell.

These extremes in the narrator's attitudes toward his Beloved and himself can basically be understood as manifestations of narcissistic love as outlined by Freudian psychoanalysts and by other schools, including the Jungians. Heinz Kohut, following Freud's analysis of narcissistic object choices in love as outlined in "On Narcissism: An Introduction," states that contrary to the general belief that a narcissistic personality does not love persons, or objects, "some of the most intense narcissistic experiences relate to objects." Kohut emphasizes that these objects of love are, however, serving functions for the person that most normal people have performed internally by a well-organized self or that the loved persons are experienced as parts of the self. For this last reason, Kohut calls the beloved persons "self-objects" in order to distinguish this kind of object from a more mature love where the other has a wholeness and integrity of its own. 35

The most generally accepted meaning of narcissism is "self-love," and Kohut creates two poles of self-love on the model of two kinds of perfection. One can say, "I am perfect" or "You are perfect, but I am part of you." From the first narcissistic perfection, Kohut derives the "grandiose self," which is both grandiose and exhibitionistic, and from the second, "the omnipotent object," or "the idealized parent imago." These are often the two extremes of narcissistic love and its objects of love. 36 The narrator's love for his Beloved predominately is at the "omnipotent object" pole of narcissistic love choice, for he completely idealizes his Beloved. Kohut calls this love an "idealizing transference." 37

This idealizing transference and the narrator's making his Beloved all powerful, perfect, and goddess-like, match greatly Jung's analysis of the transference in psychoanalysis and alchemy and Jung's use of the terms kinship libido and endogamous relationships. The foundation for Freud's, Jung's, and Kohut's ideas about transference, or the intense love (and often hate) that appears between the doctor and his patient or those in the most intense love relationship, is projection. The person projects his internal contents such as the anima onto another person who acts as a screen for the projection.

Lipot Szondi, a prominent European analyst, has examined extensively the process of projection as an unconscious ego function. He does not dispute the basic findings of Freud and Jung but tries to correlate them into his own systematic analysis of human drives and ego defenses against them. There are basically three models for the transference situation. One is the collective model of the primitives' relationships to objects, which has been most extensively examined by Lévy-Bruhl and which he calls participation mystique. 38 A second model is the state of the ego in childhood just after the period at which the child realizes he is separate from the mother. Szondi calls this the "Autistic Ego." 39 This parallels Freud's personal unconscious, just as the first model comes from Jung's collective unconscious. A third model's source is from Szondi's Familial Unconscious which does not greatly concern us here. 40 The point of Szondi's third model is that Szondi removes the word mystique from Lévy-Bruhl's participation mystique and replaces it with the word real. To retain the word mystique in an analysis of Rossetti's sonnets would introject mysticism into the interpretation of his sonnets; this is far from the case. Jung's concepts are not mystical either, since he bases the archetypes on the instincts.

Lévy-Bruhl's analysis of participation mystique, however, is important for understanding the narcissistic implications of the participation, or union. In the primitives' world, two heterogeneous things, such as subject and object of any kind, have to be joined together by some mysterious power. Thus, a union is formed and each separate object participates, or shares, in the other. The subject and object may not be distinguished from one another. Subject and object have the same identity. Yet this is also a partial identity, for each has his separate existence. Lévy-Bruhl finds an aprioristic union of subject and object, much like Jung's concept of archetypes and Wordsworth's concept of the soul in "Intimations of Immortality From Recollections of Early Childhood." In participation mystique kinship relationships are all important, and the group is more important than the individual. All the primitives' own powers are projected onto his objects in his world; they are omnipotent. A twist occurs in this participation, or union, with the omnipotent object. The primitive's own power is expanded by his participation with the powerful other, be it a totem animal, an inanimate object, a medicine man, a chief, or god. 41 The most basic model of all participation is the union of mother and child, where the mother has all power and the child is powerless. In Kohut's terms, the child would try to maintain a continuous union with its "omnipotent object," or "idealized parent imago. 42 Jung would see the situation as a man's fascination with his own anima, and, thus, the power of life and the unconscious. Szondi calls the original participation "the dual union"--a concept he adopted from the psychoanalyst Imre Hermann. 43

The narrator of The House of Life has the same attitudes as these toward his Beloved. As has been shown, the first thirty-six sonnets portray the union of the narrator and his Beloved. The first twelve sonnets portray the union at its height, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. "The Kiss" (VI) is the focal point for this heightened union of mind, body, and soul. During this segment, the narrator and his Beloved merge together and are one. The next twelve sonnets from thirteen through twenty-four show a gradual withdrawal from this oneness to a series of comparisons between their own situations or the Beloved's and the external world. In "Youth's Antiphony" (XIII), their closeness as lovers in the octave is contrasted in the sestet with "the world's throng, / Work, contest, fame, all life's confederate pleas." "Youth's Spring-Tribute" (XIV) contrasts their love in spring with the possibility of threats to their love that will appear in the winter. As we have seen, "The Birth-Bond" (XV) contrasts kindred in blood and spirit with strangers or non-kindred. The contrasts continue, noting places that do and do not contain the Beloved, nature's beauty opposing his Beloved's beauty, this present time and another time, the Beloved's optimism with his pessimism, sensuous love versus spiritual love and so on. The series conclude with a contrast in "Pride of Youth" (XXIV) between "Old Love" and "New Love." The last twelve sonnets from twenty-five through thirty-six emphasize the ideal aspects of the narrator's Beloved. Cosmic, universal, and cultural images such as "Soul-Light," "Moonstar," "Last Fire" are numerous.

Throughout all phases of the idealized union of narrator and his Beloved, one set of related images occurs constantly. In the Narcissus myth, Nemesis prepared an isolated grove for Narcissus and his own image. This place was separated from the rest of the world and had a mysterious stillness about it. Love's throne as depicted in the first sonnet "Love Enthroned" was in such a place: "Love's throne was not with these [i.e. "all kindred Powers"]; but far above / All passionate wind of welcome and farewell / He sat in breathless bowers they dream not of." In a union of participation, the united are separated from the world outside. In "Bridal Birth" (II) the narrator tells of Love's preparations of a special place for them, "Now, shadowed by his wings, our faces yearn / Together, as his full-grown feet now range / The grove, and his warm hands our couch prepare." Love does the same in "Love's Lovers" (VIII) and prepares "His bower of unimagined flowers and tree" for the Beloved. In "Passion and Worship" (IX), it is "Love's Worship" who is to be found "where wan water trembles in the grove," whereas "Passion of Love" walks "the sunlit sea." The excessive idealization of Love's Worship belongs in a narcissistic-like grove. "Silent Noon" (XIX) portrays the lovers in an open field, yet it is their "nest" since time has essentially stopped for them because of their love. This is one of the "moment's" monuments mentioned in the introductory sonnet. The title of "Heart's Haven" (XXII) gives another image of the isolated quality of their love for each other. An hour is like a bird that passes "The rustling covert" of the narrator's soul in "Winged Hours" (XXV). Sanctuary and "alcove" appear in "Her Gifts" (XXXI) and "Equal Troth" (XXXII). In "Lamp's Shrine" (XXXV), the narrator's heart becomes a "low vault" for his Beloved's "flashing jewel."

Within the narrow circle of their love, the narrator sometimes undergoes a transformation from his role as admiring but undeserving lover into an equal to the Beloved, Love, and the gods. In "The Kiss" (VI), the narrator experiences a climb from the mental state of a child through man and spirit to that of a god. A similar transformation occurs in "The Dark Glass" (XXXIV), where the narrator first compares himself to a lowly "murmuring shell" and a "little heart-flame." Then a great source of power is opened to him by the gaze of his Beloved's eyes: "Yet through thine eyes he [i.e., Love] grants me clearest call and veriest touch of powers primordial / That any hour-girt life may understand." He is touched by primordial powers of an absolute, or universal, nature. At the height of their union, the narrator does not feel anything but ecstasy, and as in "Nuptial Sleep" (VIa) both lovers sink deeper than "the tide of dreams" and are merged into a silent and imageless world. In "The Kiss" (VI) they merge together in their passion as "Fire within fire." Once beyond this state, the narrator stands off and contemplates his Beloved or her image as he does in "The Portrait" (X) or even admires another kind of image, or symbol, her handwriting, in "The Love-Letter" (XI).

Then he passes on to a stage of seeing himself mirrored in her some way in a manner quite similar to Narcissus gazing at his own image in a pool. In "The Lovers' Walk" (XII), the narrator indicates that both lovers are "mirrored eyes in eyes." The moments of this awareness of the mirror image of himself is rare in his great participation and union with his Beloved. In "Mid-Rapture" (XXVI), the narrator reaches a peak of adoration of his Beloved and as part of a question sees himself mirrored in his Beloved's eyes:

What word can answer to thy word,--what gaze

To thine, which now absorbs within its sphere

My worshiping face, till I am mirrored there

Light-circled in a heaven of deep-drawn rays?

At this moment, the narrator is aware that he participates in his Beloved's nature and being. The mirroring of the image indicates, too, the basic identity of the two personalities and the projecting of his own qualities, particularly his anima, upon the Beloved.

The mirror image has always had close associations with the double and the soul. 44 As Lévy-Bruhl has demonstrated, primitives project their own powers onto the objects, persons, and gods and thus at this stage feel powerless. But once the primitive realizes he is separate, as the narrator does when he sees the mirror image of himself in his Beloved's eyes or contemplates her at a distance in space and time, then he can become aware of his sharing in the powers of the other. This is the situation in "The Dark Glass" (XXXIV), as earlier indicated, where the narrator feels the "veriest touch of powers primordial." Through participation--for the primitives it is a participation mystique--the narrator shares in the powers and perfections of his Beloved. He is in a dual-union with her. In this state all his incompleteness, imperfections, and separateness are perfectly complemented by the missing half of his nature, which the Beloved supplies. Lipot Szondi describes this whole process of participation as the striving to be one and the same with the person. 45

To share in the other's powers and perfections, however, calls for the opposite of projection. The projected contents must be reincorporated, or introjected, by the unconscious ego. The primitive who has projected his powers onto another, thus, gets back the same powers. The most primitive example is the cannibal who only devours his most formidable enemies in order to absorb their fighting strength and power. This process can occur simultaneously and thus is called introprojection. Lipot Szondi has named this state of the ego both the "Autistic Ego" and the "cosmodualistic Ego." Ironically, this mental state of the ego is a condition of the ego's feeling absolute omnipotence over the whole universe. The ego incorporates, or introjects, all the objects of the universe, which have already received all his projections of his own powers from the unconscious. And in the unconscious, powers are limitless. The ego is a cosmodualistic ego since it participates in a dual union with the cosmos and feels as powerful as the universe.

A key factor in this ego state and Lévy-Bruhl's participation mystique is that there must be a feeling of an aprioristic union of subject and object. 46 In the narrator's situation in The House of Life he feels a spiritual "Birth-Bond" to his Beloved. In Jung's transference, the archetype of the anima-animus sexual union, or syzygy, is the aprioristic element." In Freud's transference, it is the oedipal complex of childhood that causes the transference. And Lipot Szondi's "Autistic Ego" state is based on the aprioristic presence of mutual family-type members carried in the genes of each member united in a "real" participation.

Heinz Kohut's two self-objects of omnipotent object, or idealized parent imago, and the grandiose self belong to the same process. Kohut indicates that the two self-objects can quickly change positions; thus, a narcissistic personality can idealize an object completely and then ignore it absolutely by taking back all the perfections given to the object back to himself, becoming a grandiose self. 47 In the case of primitives, their cultural and religious beliefs keep them from consciously becoming aware of their projections and ultimately the omnipotent feelings that they personally have. They only see their power as coming from outside. Kohut states that the idealization of the superego is based on narcissistic libido rather than object libido. For this reason, the superego has an aura of absolute perfection of values. 48 However, in the case of those who like primitives at the participation mystique stage have not developed a strong internal superego, persons, objects, gods, and things can serve as self-objects in the sense of being the receiver of all perfection and powers. The period of the omnipotent object and the grandiose self is the same and occurs after a cohesive self image is formed and before a permanent superego is formed. 49

The separation of the lovers from the rest of the world into some "breathless" bower, field, grove, or nest, their union together, and the complete domination by the emotion of love--all these point to a paradise-like setting and situation. These first thirty-six sonnets have many features of a Garden of Eden. Lacking, however, in these sonnets is the sense of sin and guilt. Even the death of the first Beloved announced in "Life-in-Love" (XXXVI) offers no sense of punishment as a reason for the narrator's expulsion out of his Garden of Eden. The presence of Love, or Eros, and Rossetti's strong emphasis upon the soul points to a Greek source for an equivalent paradise. The Greek word for soul is psyche, and the Greek myth about the meaning of the soul is "Amor and Psyche" in Apuleius's book The Golden Ass. (This same tale also appears at a significant point in the development of the main character in Walter Pater's Marius, the Epicurean.)

When Psyche became a young woman, she was so beautiful that crowds of people neglected their worship of Venus to view Psyche's beauty. Venus became so angry that she sent her son Eros to punish Psyche. The curse was that Psyche would be "consumed with passion for the vilest of men. 50 This has parallels with the young men who cursed Narcissus, wanting him to be consumed with self-love that was to be frustrated. In this case Eros is carrying out Nemesis's role of preparing a place for the curse to be carried out; Venus is the real Nemesis, however. No man proposes marriage to Psyche, so her parents consult Apollo, who says that she must prepare for both death and a marriage with an immortal who is a dragon. This oracle is carried out, and in a wedding-funeral march, Psyche is led to a cliff and thrown over. But winds glide her to earth. Then she finds a "transparent fountain of glassy water" and in the heart of a grove a palace. This becomes a paradise when Eros disguised by the darkness of night comes to her couch and makes her his bride. His one admonition is that she must not strike a light. At night they are in perfect union as are the lovers in The House of Life. Every wish of Psyche's is granted--food, wealth, music, pleasure, sensual love. She is happy until she hears that her family is grieving over her supposed death. Then she wants to go to them and tell them she is alive. She even threatens suicide if she can not go. 51

Death was ever present so far in Psyche's tale of love and paradise. In The House of Life, death is present too from the very beginning. In the introductory sonnet, Death is an equal power on the other side of the coin that represents the soul. The underground world of death is evoked in Charon's image. In "Love Enthroned" (I) Life is "wreathing flowers for Death to wear." In the next sonnet "Bridal Birth," there is "Death's nuptial change." After the worshiping song of praise in the octave of "Lovesight" (IV), the narrator fears he will no longer see "the shadow of thee [i.e., the Beloved], Nor image of thine eyes in any spring." "Death's imperishable wing" is nearby. Even in "The Kiss" (VI) the thought of "death's sick delay" and the image of Orpheus coming out of the region of death with his Beloved behind him precedes the ecstasy of the kiss. The thirty-six sonnets close with the death of the first Beloved in "Life-in-Love" and the introduction of the second Beloved. Death has appeared at or close to the moments of greatest pleasure and ecstasy of love. The significance of the close relationship of death and love in connection to the character of Love and narcissism will not be clear until Death's full appearance in "Death-in-Love" (XLVIII) and his pervasiveness in the Willowwood sonnets. The paradise-like union between the narrator and his first Beloved that has a narcissistic underpinning is over and a new transformation awaits him.

NOTES

1Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. Rolfe Humphries (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1957), p. 73.

2Hyman Spotnitz and Philip Resnikoff, "The Myths of Narcissus," Psychoanalytic Review, 41 (1954), 177.

3Robert Stein, Incest and Human Love (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1974), p. xiii.

4Arthur C. Benson, Rossetti (London: Macmillan, 1904), p. 129; Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The House of Life: A Sonnet Sequence, ed. Paull Franklin Baum (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1928), p. 35. "Stillborn Love" (LV) contains the phrase "the house of Love."

5The Collected Works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ed. William M. Rossetti (London: Ellis, 1911), p. 608.

6Oswald Doughty in A Victorian Romantic: Dante Gabriel Rossetti (London: Frederick Muller, 1949) and David Sonstroem in Rossetti and the Fair Lady (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1970) particularly explore the women in Rossetti's life as means to interpret his poetry.

7Gelpi, "The Image of the Anima in the Work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti," The Victorian Newsletter, #45 (1974), 1; Hyder, "Rossetti's Rose Mary: A Study in the Occult," Victorian Poetry, 1 (1963), 197.

8The Collected Works of D. G. Rossetti, p. 555.

9Carl Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (New York: Pantheon Books, 1959), pp. 3-5.

10Jung's first book in 1912 then entitled Psychology of the Unconscious and later in 1952 entitled Symbols of Transformation (New York: Pantheon Books, 1956) introduced his concepts that the libido was not primarily sexual as Freud contended but was general psychic energy and that this unconscious energy appeared in consciousness as symbols. Jung further established the spiritual significance of incest figures such as the hero returning to the mother symbolically by entering the whale, or womb, and then fighting his way out to a higher state of consciousness. Jung thus interpreted Frobenus's "night sea journey" in spiritual and symbolic terms rather than as a Freudian personal unconscious manifestation of an incestuous sexual union with the mother. pp. 210-212.

11Jung, The Archetypes, pp. 26-28.

12Ibid., p. 32.

13E. R. Dodds, Greeks and the Irrational (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), pp. 15-16.

14Jung, The Archetypes, pp. 43-44.

15Ibid., pp. 65-66. Lipot Szondi [Experimental Diagnostics of Drives, trans. Gertrude Aull (New York: Grune & Stratton, 1952)] is the founder of Schicksalsanalyse (or Fate-Analysis) and believes, as Jung does ultimately, in the existence of both the Freudian personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. Szondi, however, sees the archetypes as a rational and symbolic representation of the instincts or drives and adds another layer to the unconscious which he calls the Familial Unconscious. This is the source for particular drives that are passed on by the genes of particular family members to their offspring. His work traces the transformations of instincts into sexual areas, mental pathologies, archetypes, and cultural forms.

16Carl Jung, "Psychology of the Transference," The Practice of Psychotherapy (New York: Pantheon Books, 1954), pp. 167-175.

17Ibid., pp. 219-220.

18Ibid., pp. 224-225.

19Ibid., pp. 226-231.

20The Collected Works of D. G. Rossetti, p. 558.

21Ibid., p. 417.

22Ibid., p. 420.

23Benson, Rossetti, p. 47; Virginia Surtees, The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882): A Catalogue Raisonné (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), p. 74 and Plate 182.

24Surtees, Paintings and Drawings, pp. 93-94 and Plate 238; Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family Letters: With a Memoir by William Michael Rossetti (1895; rpt. New York: Ams Press, 1970), 1, p. 173.

25Doughty, A Victorian Romantic, p. 265.

26Family Letters, I, p. 173.

27Doughty, A Victorian Romantic, p. 270; Family Letters, I, p. 208.

28Sydney E. Pulver ("Narcissism: The Term and the Concept," Journal of American Psychoanalytic Association, 18 [1970], 320-323) presents the history of the evolution of the term narcissism from general usage to Freud's specific definition in his 1914 essay on narcissism.

29Sigmund Freud, "On Narcissism: An Introduction," Collected Papers, 4 (1914; rpt. New York: Basic Books, 1959), p. 47.

30Ibid.

31John E. Gedo and Arnold Goldberg, Models of the Mind: A Psychoanalytic Theory (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1973), p. 67. These authors give psychoanalytical models of the mind which include both a narcissistic love and an object love development on the model of Eric H. Erikson's "epigenetic schema" in his book Childhood and Society but confined to the internal structure of the mind.

32Heinz Kohut, The Analysis of the Self: A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders (New York: International Universities Press, 1971), p. 33.

33James Hillman, "The Feeling Function," Lectures on Jung's Typology (New York: Spring Publications, 1971), pp. 113-129.

34Ernest Cassirier, Language and Myth (1946; rpt. New York: Dover Publications, 1953), pp. 33-36.

35Kohut, Analysis of Self, p. xiv.

36Ibid., pp. 9-27; Grace Stuart in Narcissus: A Psychological Study of Self-Love (New York: Macmillan, 1955) presents a psychoanalytical study of the Narcissus myth without the clinical emphasis of Kohut's works. She uses literary sources to support her concepts. She and Kohut agree on all major points.

37Kohut, Analysis of Self, p. 37.

38Lipot Szondi, Ich-Analyse: Die Grundlage zur Vereinigung der Tiefenpsychologie (Bern: Hans Huber, 1956), p. 166.

39Szondi, Experimental Diagnostics of Drives, pp. 127-130.

40Szondi, Ich-Analyse, pp. 172-174; Schicksalsanalyse: Wahl in Liebe, Freundschaft, Beruf Krankheit und Tod, 3rd ed. (1944; rpt. Basil: Schwabe, 1965), pp. 15-18.

41Szondi, Ich-Analyse, pp. 166-170; Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, The "Soul" of the Primitive (1927; rpt. Chicago, Henry Regnery, 1966).

42Kohut, Analysis of Self, p. 37.

43Lipot Szondi, Triebpathologie: Elemente der exakten Triebpsychologie und Triebpsychiatrie (Bern: Hans Huber, 1952), p. 419.

44Paula Elkisch, "The Psychological Significance of the Mirror," Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 5 (1957), 235.

45Szondi, Ich-Analyse, p. 172.

46Szondi, Experimental Diagnostics of Drives, pp. 127-130.

47Kohut, Analysis of Self, p. 92.

48Ibid., pp. 41-42.

49Gedo and Goldberg, Models of the Mind, pp. 81-86.

50Erich Neumann, Amor and Psyche: The Psychic Development of the Feminine: A Commentary on the Tale by Apuleius (Princeton University Press, 1956), p. 5. This book is divided into one part as the original tale and one part as commentary.

51Ibid., pp. 3-13.

CHAPTER II

Darkened Love and Wild Images of Death

In "Pride of Youth" (XXIV), which is two-thirds the way through the first group of thirty-six sonnets, the narrator glimpses a view of life that contradicts his absolute faithfulness to his Beloved and his glorification of her. The narrator compares a child who reacts indifferently to someone's death to a "New Love" who quickly forgets an "Old Love." The comparison is extended to the "proud Youth" who is the bearer of this New Love. The Youth goes from one love to another as rapidly as a devout person counts the beads of a rosary while saying his prayers. The religious image of a rosary links the fickle Youth to the narrator's own religious devotion toward his Beloved and his idealization of her. The narrator particularly displayed his veneration of her in "Love's Testament" (III), "Lovesight" (IV), "Passion and Worship" (IX), and "The Lamp's Shrine" (XXXV).

This devotion to the Beloved ends when the narrator announces both the death of his first Beloved, or Old Love, and the presence of his second Beloved, or New Love, in "Life-in-Love" (XXXVI). Unlike the child in "Pride of Youth" (XXIV), who gives the death of another person little thought, the narrator has greatly suffered from the death of his first Beloved. His own life has, in a sense, departed from him, and he only finds it in his new Beloved. He says to himself, "Not in thy body is thy life at all, / But in this lady's lips and hands and eyes." Before, he has been "sorrow's servant and death's thrall." Yet the narrator reacts like the proud Youth in that he has found a new Beloved. The brief span of the new love affair which is fully presented in the twelve sonnets after "Life-in-Love" (XXXVI) from sonnets thirty-seven through forty-eight strongly suggests that this process of replacing one Beloved by another might continue in the rapid manner of a worshiper counting the beads of his rosary. During his second love affair, the narrator will dimly begin to perceive the narcissistic nature of his love that will create emotional turmoil for him. Only in the Willowwood sequence will there be offered a possible way out of this potentially relentless exchange of one Beloved for another.

Death completely surrounds and pervades these twelve sonnets portraying the narrator's love for his second Beloved. The title of the sonnet "Life-in-Love" (XXXVI), which precedes this group of sonnets, is matched by this section's concluding sonnet entitled "Death-in-Love" (XLVIII). In essence, Death has been substituted for Life. The Willowwood sonnets immediately following the experience of the New Love deal explicitly with death. Love whom the narrator worshiped in the first thirty-six sonnets through his love for his first Beloved has somehow become transformed by the end of his second love into Death itself. This strange development has close ties to the intimate connection of death and love in the Narcissus myth and the psychology and archetypes associated with it. From the very introductory sonnet, Death has always been present, sometimes explicitly and at other times only indirectly or in a metaphoric sense. Death, however, completely permeates these last twelve sonnets before the Willowwood sonnets in which is achieved a climax for Part I of The House of Life.